Home Selling Step 2: Understand Your Net Proceeds From Selling Your Home

If you are calculating net proceeds from selling your home, this step is where you stop guessing and start working with real numbers. The purpose is simple:

After selling costs, what do you actually walk away with—and is it enough for what comes next?

This is not the step where you celebrate equity. It’s the step where you verify whether that equity is usable, and whether selling improves your position or quietly weakens it.

This Step Only Makes Sense If Credit and Budget Allow

Before we touch closing costs, we need to re-anchor to the same fundamentals that apply on the buying side. If you already own a home, selling and buying are tied together. You don’t get to skip the basics just because you’re “moving up” or “downsizing.”

- If your credit has worsened since you bought, selling and rebuying becomes more expensive. A lower score can push you into worse rate tiers, higher payments, and tighter underwriting.

- If interest rates have gone up, the same house now costs materially more per month—sometimes shockingly more—without the house being any different.

- If your cash flow is already tight, selling doesn’t reset that reality. It exposes it.

If you need to revisit the foundation, start here:

- Home Buying Step 1: Know Your Credit

- Home Buying Step 2: Build a Sustainable Budget

- Home Selling Step 1: Deciding Whether to Sell Your Home (and Whether It Makes Sense)

If credit and budget don’t support the move, the math below is a warning—not an invitation.

Gross Sale Price vs. Net Proceeds: Why the Number Matters

The number people talk about is the sale price. The number that matters is what you have left after the transaction is finished.

Net proceeds are not what your house sells for. Net proceeds are what remains after friction—much of which arrives all at once.

Who Should—and Should Not—Make the Sell/Buy Decision

This is an important boundary to draw clearly.

The decision to sell and buy should not be made by the real estate agent involved in the transaction. Even well-intentioned professionals operate inside incentive structures, and selling and buying—especially in close succession—creates a substantial payday for the brokerage and a very good month for the agent.

That does not mean the advice you receive is wrong. It does mean the final decision belongs to the household that will live with the outcome.

You hire a REALTOR® for market knowledge, strategy, execution, and negotiation. You do not hire them to decide whether the transaction itself improves your financial position. Those are two different roles.

Advice Is Valuable—but Real Estate Is Still Transactional

You pay your REALTOR® for their advice, experience, and professional opinion. That advice matters. But it’s important to be honest about how the industry is structured.

Real estate professionals are paid transactionally, not for advice alone. If a transaction does not happen, no one gets paid.

As a result, very few REALTORS®—even thoughtful, ethical ones—are going to tell you not to sell or not to buy unless the situation is clearly untenable. Momentum and deal flow are built into the system.

This is not unique to real estate. Brokerage firms once operated under similar incentives in the investment world, where frequent trading generated revenue for the firm and trader—not necessarily better outcomes for the investor.

That incentive mismatch is why Certified Financial Planners (CFPs®) exist. Real estate has no direct CFP-equivalent. Nearly all participants are compensated by transactions, not retained for independent financial advice.

That makes it even more important that financial decisions remain with the family involved.

Home Selling Closing Costs: The Buckets You Must Account For

Exact figures vary by transaction and lender/title company, but the categories are consistent. This is the structure you need before we ever plug numbers in.

1) Transaction Costs (Inevitable)

- Agent compensation

- Title policy / title insurance

- Escrow and settlement fees

- Recording fees

- Tax and HOA prorations (as applicable)

Net equity after selling costs (no appreciation): This table shows how much principal you’ve paid down (“equity”) versus estimated selling costs.

Important: This does not include any seller concessions, repairs, buyer credits, or unexpected transaction costs. These amortization examples are from Step one and we’re using these assumptions for the mortgage 30-year fixed, 5.00% interest.

| Year | $100,000 Example | $250,000 Example | $350,000 Example | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Equity (Principal Paid) |

Estimated Selling Costs |

Net (Equity − Costs) |

Equity (Principal Paid) |

Estimated Selling Costs |

Net (Equity − Costs) |

Equity (Principal Paid) |

Estimated Selling Costs |

Net (Equity − Costs) |

|

| 1 | $1,475 | $7,717 | -$6,242 | $3,688 | $17,508 | -$13,820 | $5,164 | $24,035 | -$18,871 |

| 3 | $4,656 | $7,717 | -$3,061 | $11,641 | $17,508 | -$5,867 | $16,297 | $24,035 | -$7,738 |

| 5 | $8,171 | $7,717 | $454 | $20,428 | $17,508 | $2,920 | $28,599 | $24,035 | $4,564 |

How to read “Net”: If “Net” is negative, selling at that point means your principal paydown has not yet covered estimated selling costs (before any concessions).

This table is intentionally conservative in one direction and liberal in another. It is conservative because it assumes no appreciation at all, even though most homes gain value over time if they are maintained. At the same time, it is liberal because it assumes no seller concessions whatsoever. In the real world, concessions are common and range widely—from a modest $600 home warranty to a five-figure repair or replacement (sewer line failure, foundation work, roof replacement, or major HVAC issues). Those costs come directly out of your proceeds.

That’s why this table should be read as a best-case baseline, not a worst-case warning. If you do not have roughly 10% of your home’s value in equity after closing costs, the financially honest answer is usually: don’t sell unless you have to. Selling too early often converts what feels like “equity” into a realized loss once transaction friction is applied.

And the real answer: if you run the amortization tables out and let the math find the answer, you will have enough equity to cover these sample closing costs with a 10% value cushion by years 9 or 10.

Realistically, if your home appreciates in value, this should happen sooner. Which is where we end up at that 7-year home trading cycle. But at 7 years, you’re not making a huge profit, you’re getting out of your home with a cushion that 1 unexpected major repair could destroy.

There are exceptions. If your circumstances have changed and you can no longer afford the payments, exiting at a controlled, limited loss—sometimes with lender cooperation—is almost always better than allowing the home to slide toward foreclosure. That is a different conversation, with different tools and priorities, and it deserves its own discussion.

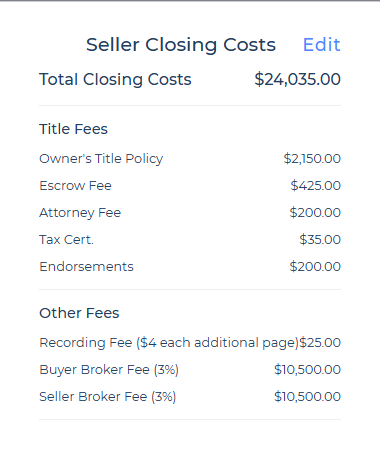

Example seller closing costs for a $350,000 home sale, illustrating how commissions, title fees, and other expenses affect net proceeds. These examples reflect typical Texas closing cost structures and will vary by transaction.

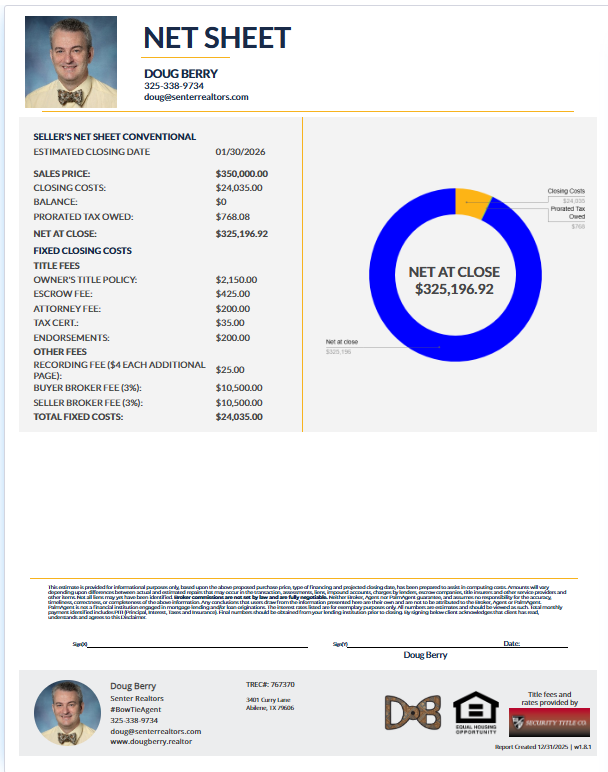

Example seller net sheet for a $350,000 home sale with no loan payoff, illustrating estimated closing costs and net proceeds at closing. These examples reflect typical Texas closing cost structures and will vary by transaction.

2) Market-Driven Costs (Often Underestimated)

- Buyer concessions

- Inspection-related repairs or credits

- Appraisal-driven renegotiation

3) Preparation and Exit Costs (Frequently Ignored)

- Pre-list repairs and cleanup

- Staging or preparation expenses (even if minimal)

- Moving costs

- Temporary housing, storage, or overlap expenses

Equity Compression: Where Expectations Break Down

Even when your home sells at a “good” price, it is common for sellers to be surprised by how much equity gets consumed by the transaction. The reason is simple:

- Costs don’t arrive gradually. They arrive at once.

- Repairs and credits hit right when you’re trying to preserve proceeds.

- And if you are selling and buying, you may pay transaction friction twice in a short period.

This is why calculating net proceeds from selling your home needs to happen early. It’s the only way to prevent a move that looks good on paper but reduces your flexibility in real life.

Sellers often assume net proceeds are stable once an offer is accepted. In reality, the equity you see at acceptance represents a best-case snapshot, not a guaranteed outcome. Later steps in this series show where and how those proceeds are commonly eroded before funds are actually in hand.

The Down Payment Question Most Sellers Don’t Ask Soon Enough

Here’s the question that separates careful planning from wishful thinking:

If selling consumes most of your equity, where does the next down payment come from?

If you’re counting on rolling equity forward, you need to know what you’ll actually have available after commissions, closing costs, repairs, and concessions. Smaller down payments can mean higher payments, mortgage insurance, or worse pricing—especially if credit has slipped.

The Proper Decision Loop for Selling and Buying

Because selling and buying affect multiple parts of your financial life, the decision should not live with any single professional.

A sound decision loop looks like this:

- The Household: You decide whether the tradeoffs make sense. Lifestyle impact, risk tolerance, timing, and flexibility all live here.

- Your Accountant or Tax Advisor: Especially important if you’ve moved frequently, converted a home to a rental, inherited property, or are unsure about capital gains exposure.

- Your Banker or Lender: This is critical. They see how credit tiers, interest rates, debt-to-income ratios, and down payments actually affect your buying power after a sale.

- Your REALTOR®: Once the decision is made, this is where execution, pricing, negotiation, and market strategy belong.

When those roles are respected, decisions improve—and surprises decrease.

Timing Matters: When Sellers Actually Receive Their Money

In the buying series, I emphasize that buyers don’t truly have the keys until closing and funding are complete. The same timing reality applies on the selling side:

Sellers receive funds after closing and funding—and then there is still practical timing: the wire/e-transfer has to land, or a paper check must be issued and deposited. Do not plan your life around the assumption that money appears instantly because you signed paperwork.

Late closes are not uncommon, and last-minute issues happen. That’s why timing and contingency planning matter just as much as “what it sells for.”

Deals Can Fall Apart Late: Protect the Next Move

One of the most common procedural mistakes sellers make is treating a transaction as complete before it has actually closed and funded.

Contracts can unravel late due to financing failures, appraisal issues, title defects, inspection renegotiations, or a party simply failing to perform. Until funds are disbursed, proceeds are hypothetical—not usable.

If you are buying another home, this is why your offer structure matters:

- Do not rely on proceeds that have not closed and funded.

- Contingencies should be tied explicitly to the successful closing and funding of the sale.

- If the sale does not close, you need a defined exit that prevents forced decisions or legal exposure.

This is not pessimism. It is transaction risk management.

Capital Gains: Light Touch, Real Awareness

In most Abilene-area transactions, capital gains taxes are not a major factor because price points and typical appreciation patterns don’t often create taxable gains for owner-occupants. That said, there are exceptions—especially for people who buy and sell primary residences frequently, convert homes to rentals, or do repeated short-horizon moves.

This is not tax advice. If you think your situation might be unusual, talk to a CPA before you make decisions based on assumptions.

Emotional Momentum Is Not Financial Readiness

Many sell-and-buy decisions are driven by emotion rather than math:

- “We’ve waited long enough.”

- “Everyone else is moving.”

- “We don’t want to miss out.”

Emotional readiness and financial readiness are not the same thing. Both matter—but they should not be confused.

This step exists to slow momentum long enough for clarity to catch up. Activity can feel like progress even when it isn’t.

FOMO Is a Dangerous Mindset at This Stage

Fear of missing out is one of the most destructive forces in housing decisions—especially when selling and buying are linked.

At this stage, activity can feel like progress even when it isn’t. Urgency, comparison, and perceived scarcity push people to reset housing decisions prematurely, trading long-term compounding for short-term emotion.

The damage here is rarely immediate. It shows up later as:

- reduced flexibility,

- thinner safety margins,

- and repeated transaction friction that quietly erodes wealth.

A primary residence is not just shelter. Over time, it is one of the most common vehicles for intergenerational stability. That outcome depends far more on time and discipline than on perfect timing.

This step exists to slow momentum long enough for clarity to catch up.

Choosing Not to Sell Is Not Defeat

If the math doesn’t work, that is not failure—it’s information.

Sometimes the most rational move is to step back and improve the home you already own in ways that improve livability and reduce stress:

- Minor reconfigurations or small additions that solve functional problems

- Outdoor living improvements that make the property more usable day-to-day

- Insulation, windows/doors, or HVAC upgrades if maintenance and utility costs are the real issue

But don’t confuse these investments with guaranteed resale returns. You are correcting negatives that affect you now and making the home more agreeable to you. Some improvements preserve value or reduce objections later, but they should be justified as quality-of-life and stability decisions—not resale fantasy.

What This Step Is Designed to Prevent

- Overestimating usable equity

- Underestimating the friction of selling

- Assuming selling automatically improves your position

- Making a move that works on paper but collapses under timing and cash flow reality

What Comes Next

If selling still makes sense after you understand your net proceeds from selling your home, the next step is to prepare the asset the right way—only after the math supports the move.

That’s where we go in Home Selling Step 3.

About Me — Doug Berry, MBA, REALTOR®

The Bow Tie Agent

I’m a REALTOR® with Better Homes & Gardens Senter, REALTORS® who focuses on helping buyers understand the real-world side of homeownership — from lending and budgeting to navigating underwriting without surprises. With an MBA and experience as a lender with USDA Rural Development’s mortgage programs, I approach the process the same way I do with clients: clearly, calmly, and without sales pressure.

If you have questions, need help figuring out where you are in the process, or want a second set of eyes before making a move, feel free to reach out:

📧 Doug@senterrealtors.com

📞 325-338-9734

🌐 www.dougberry.realtor

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link